Polish community takes hold

This is an excerpt from “Faith and Family,” 150 Years of History and Tales of the Ed & Irene (Lamie) Fleis Family in Leelanau County, by Ruth Ann Smith. Continued from Dec. 19

When Tomasz left his homeland, he left behind Jozefina, whom he dearly loved. Now that they were reunited after a long absence, he hoped to marry her soon, but after hearing good news of homesteading in northern Michigan, the couple decided to wait.

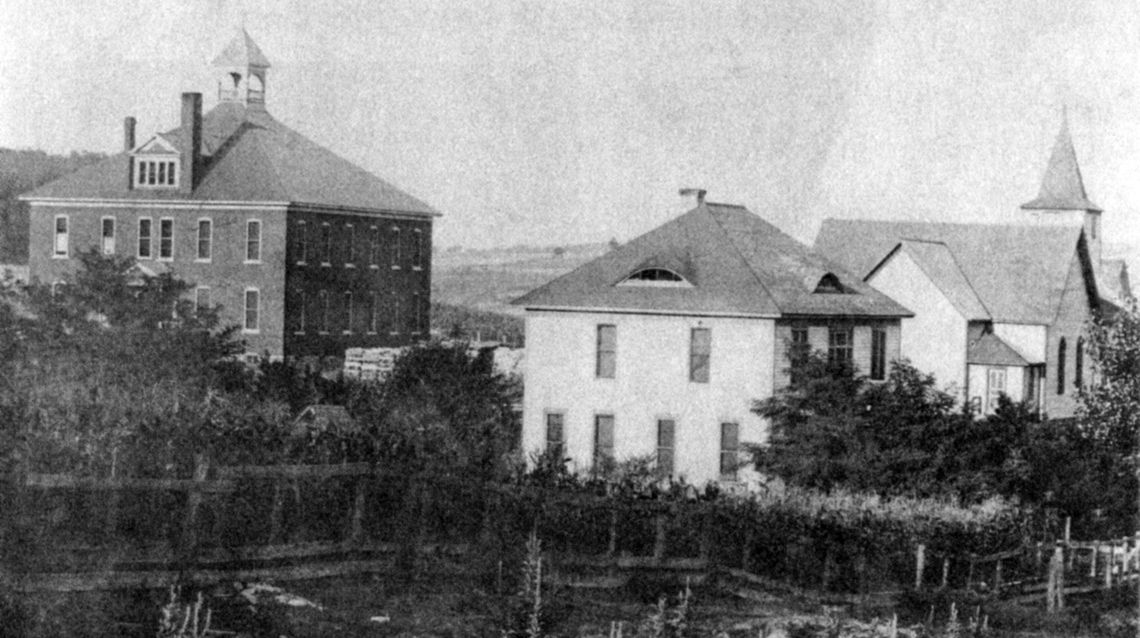

Many Poles who had initially settled in Milwaukee had already traveled to northern Michigan after hearing of land available there for farming. A small booklet published in 1998 upon the centennial of Holy Rosary School in Isadore says of the earliest settlers, “After a couple of years in the area, some returned to Michigan and explained how land could be gotten for the asking.”

The Fleis and Kelinski families heard such talk and decided it was time to make the bold move to leave Milwaukee and plan a journey to Leelanau.

First to arrive was Tomasz’s sister, Marianna, and her husband, Adam Cerkowski, in 1874. Then, Tomasz and Jozefina, two of his brother, and his sister-inlaw, her parents, and a large group of Polish immigrants steamed across Lake Michigan to Manistee, then to Centerville Township, Leelanau County, in the late fall of 1875.

A Holy Rosary School’s 1898 -1998 booklet indicated, “When the ship docked at Good Harbor, there were no state roads — only one-lane trails dotted with three stumps which were muddy in the spring and nearly impassable in winter.”

They would have carried their belongings as they walked the three miles to a little community that had sprung up by the railroad tracks.

The same booklet stated, “Later, when a post office was established, this area was named Isadore, after the patron saint of farmers…” It was one of three local areas Poles would settle, the other two being nearby: Schomberg and Bodus.

Another parish booklet, Holy Rosary Catholic Church, 18831983, stated, “Treaties with the Indians, and the Homestead Act, which had taken effect just a dozen years earlier, on Jan. 1, 1863, opened America’s heartland to emigrating families.”

The Homestead Law was signed on May 20, 1862, by President Abraham Lincoln. A settler could acquire 160 acres, free of all charged except a minor fee when filing a claim, and must live on the land five years before getting title.

Improvements needed to be made; a house built, as well as well dug; 10 acres plowed, and a specified amount of land fenced. For $1.25 per acre, a settled could even obtain the land after only six months of residence.”

Jozefina’s parents, John and Susanna Kelinski, and Tomasz’s sister and brother-in-law. Marianna and Adam Cerkowski, aligned their 60 and 80-acre claims near the site where Tomasz staked his 160-acre claim, described with Centerville Township’s 1900 plat book.

The Polish settlers came with deep religious and community values. Foremost, they wanted their own church and school so they could worship and educate their children to their native language. An Aug. 28, 1948, Leelanau Enterprise article “History of Holy Rosary Church, Isadore,” reprinted on March 2, 2017, providing the following: “In the beginning, missionaries like Father Frederic Baraga (later elevated to bishop), Father Mrak, and Father Zorn helped the families carry on their faith and culture. They travel alone by pony, or on foot from Petoskey and even the Upper Peninsula, and in the winter on showshoes or by dogsled. As soon as a missionary arrived, people would gather in a private home, where he would offer the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, and people would receive the sacraments.”

On Jan. 10, 1876, Tomasz and Jozefina were married by a missionary. Rev. Philip L. Zorn officiated; Constantine Kelinski ) Josefina’s brother), and Mary Zin were witnesses. The ceremony might have taken place in her parents’ makeshift home, one of the private homes the community eventually used for worship, or the Gatzke home, across from what is now Holy Rosary Church.

When Tomasz applied for a 160-acre parcel on Schomberg Road, little more than a mile north of Isadore, close to Marianna and Adam, and Jozefina’s parents, he would have had to go physically into the Land Office in Traverse City on at least two occasions to make the initial entry, and then to initiate the paperwork to obtain the final grant once the requirements for residency and improvements had been satisfied. Small payments were required on both occasions. The Land Office in Traverse City was run by the same folks often believed, but by an agent in the Land Office for Traverse City was run by the same folks who ran the Grand Traverse Herald newspaper. The paperwork was then sent by the Land Office to Washington, D.C., and there it was reviewed by folks in the Land Office, and if satisfactory, a Homestead Act certificate (not actually signed by the president himself, as local folks often believed, but by an agent of the Land Office for him was mailed back to the Land Office in Traverse City, where the person picked up. (There wasn’t an inspection process or a site visit; instead, the person submitted several affidavits from neighbors with regards to his actual residence there and the improvements that he made.)