This continues a series adapted from the book, “A Port Oneida Collection,” Volume 1 of the twopart set, “Oral History, Photographs, and Maps from the Sleeping Bear Region,” produced by Tom Van Zoeren in partnership with Preserve Historic Sleeping Bear. Here we take a look at the Anderson brothers and their farm east of Lake Narada.

A pair of legendary Port Oneida characters was the bachelor brothers Henry & Ernie Anderson — for some reason generally referred to as “The Henry & The Ernie”— usually pronounced “Da Henry & De Erni,” perhaps echoing their Scandinavian accent.

Henry & Ernie’s farm had been purchased from the government by their maternal grandfather back in 1861 as a preemption claim (at a nominal cost, after occupying it.) His daughter Maggie spent her life there with her Swedish husband Gustaf Anderson, and passed it on to the two sons, who stayed for their lives.

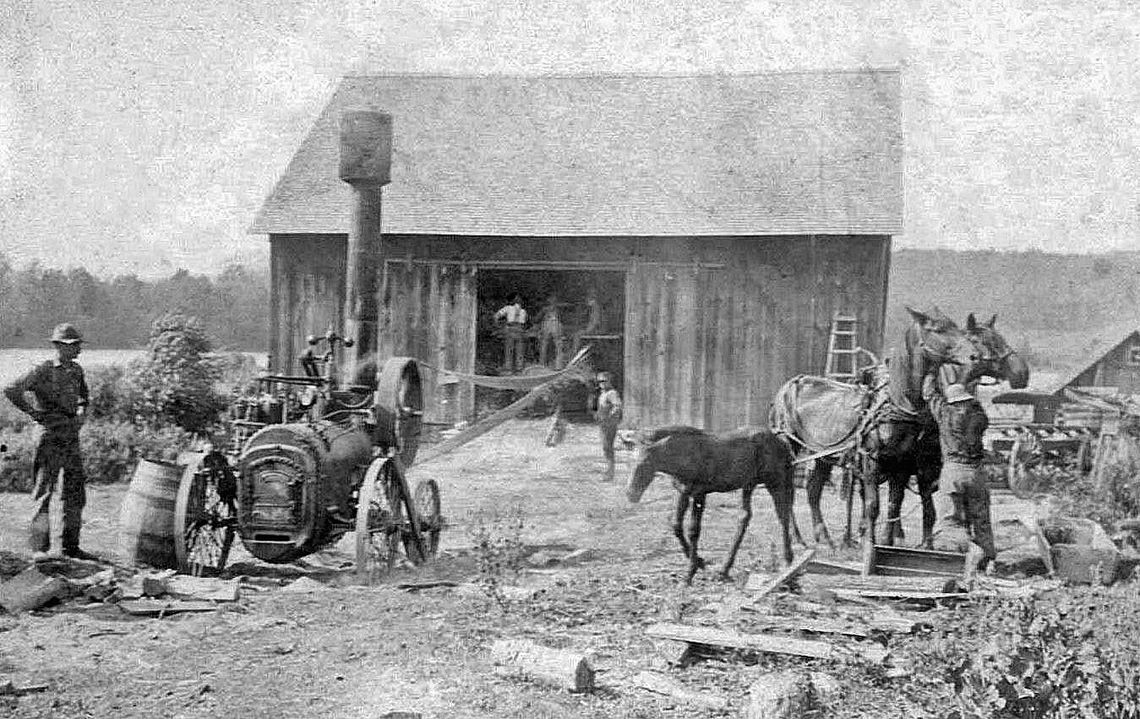

Anything involving mechanical or otherwise practical knowhow seems to have been fair game for Henry & Ernie. In addition to maintaining their farm/orchard operation, they were the ones in the community who owned and operated the monstrous steam engine-powered threshing machine (or “thrashing” machine, as was usually said here) that was hauled from farm to farm at harvest time. On the side, they also made many “beautiful” skiffs for others in the community, and assisted boat builder Fred Miller in constructing larger commercial fishing boats.

“They were awfully good blacksmiths,” according to George Burfiend. He recalled a time when a shaft broke during the thrashing bee at the Burfiend Farm. His father Howard was upset because he knew it would take a week to get a new one ordered. “They said, ‘Oh no, we’ll be back tomorrow morning.’” Howard didn’t believe it could be done; but they took the shaft home and forge-repaired it “straight as could be.”

As well as mechanical talent, The Henry & The Ernie possessed musical ability. Laura Basch recalled that at the house dances held in the community, “Henry Anderson was usually the organist and Ernie played the fiddle.”

In addition to “Da Henry & De Ernie,” the brothers had another pair of nicknames: “The Honey & The Sweety.” This, too, was never really explained. A few times during oral history interviews the question was broached as to whether they might have been thought to be homosexual; but the answer was usually along the lines of “You never thought of such a thing” at that time, or “No, I don’t think there was any such thing as homosexual in them days.” However, Don Dechow did express anger about the names, suggesting that they carried an implication that the brothers were somehow lacking in manliness — which Don said was untrue: “They were true solid men! . . . They just didn’t marry, that’s all . . . That’s my opinion. That always angered me.”

Henry & Ernie were famous for their frugality. Laura Basch remembered that “Henry would say, ‘We shall see, we shall not waste anything;’ and they never did. And he said, ‘We will fry our (salt-cured] pork first, and then we’ll fry the potatoes in it, and that way that can salt the potatoes and it won’t be any salt wasted.’” Leonard Thoreson recalled, “The story goes that when somebody was down there when they was making breakfast one morning, and I don’t know if it was Ernie or Henry was frying an egg, making breakfast. He sliced an egg in half, and they each took half. So they were pretty close.”

Another time, at the noon dinner at a thrashing bee, one of them was passed the sugar; but he responded, “No thank you. We just don’t want to get in the habit.” George Burfiend noted, though, that they generally would eat large amounts at such events; otherwise, it “didn’t seem like they had good energy because they just didn’t eat anything.” To be continued