Indigenous sovereignty was the topic of discussion at the International Affairs Forum (IAF) talk on May 16, where the public listened to Matthew Fletcher, a Harry Burns Hutchins Collegiate Professor of Law at Michigan Law School, share his insight about the background of tribes in the region and their rights today.

Fletcher teaches and writes in the areas of federal Indian law, American Indian tribal law, Anishinaabe legal and political philosophy, constitutional law, federal courts, and legal ethics. He sits as the chief justice of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, the Poarch Band of Creek Indians, and the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians (GTB).

In addition, he sits as an appellate judge for the Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, the Colorado River Indian Tribes, the Hoopa Valley Tribe, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, the Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish (Gun Lake) Band of Pottawatomi Indians, the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi Indians, the Rincon Band of Luiseno Indians, the Santee Sioux Tribe of Nebraska, and the Tulalip Tribes.

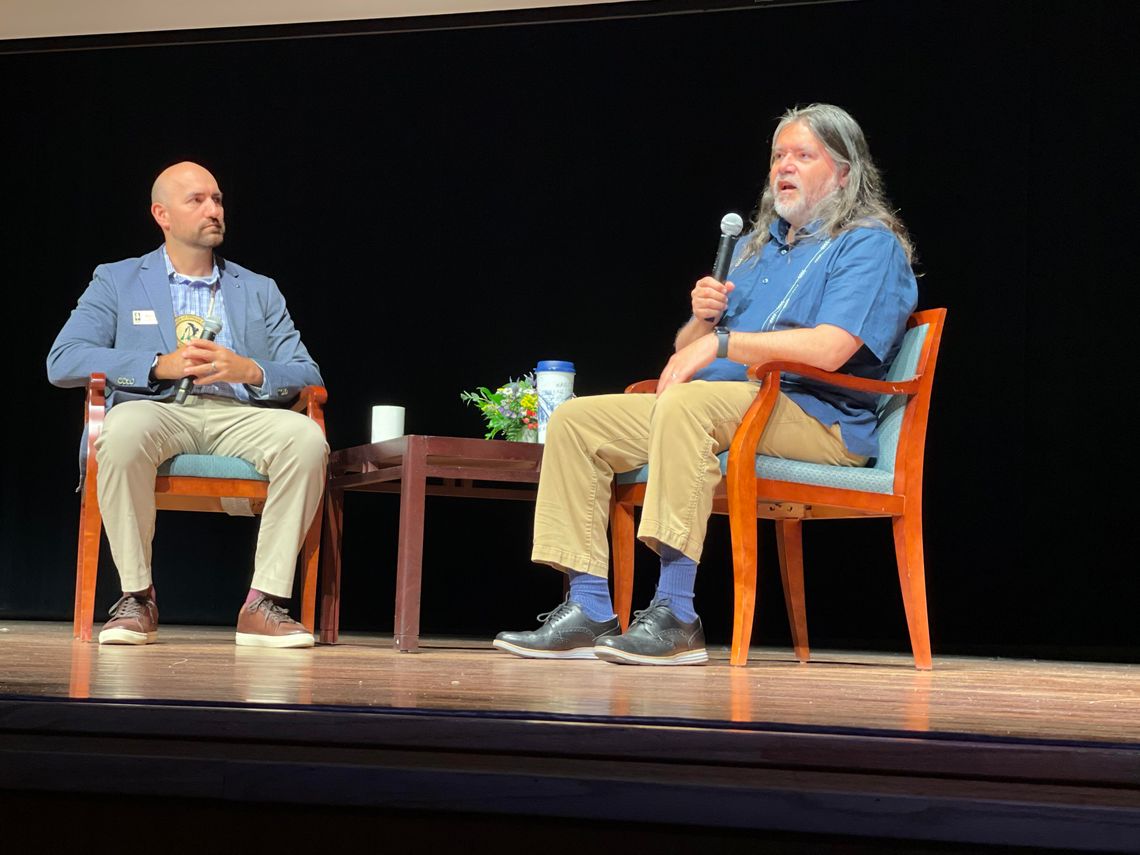

The IAF moderator, Mark Wilson, a GTB member who has also served the tribe over the years in different capacities including as vice-chair of the tribal council from 2014-2022, engaged Fletcher on critical issues pertaining to the sovereignty of indigenous peoples. The discussion started with Fletcher speaking about the Treaty of Washington, which ceded to the United States 16 million acres of land in the Upper and Lower Peninsula. The treaty of 1836 would decide hunting and fishing rights, reservation lands, and other services for the Odawa and Ojibwe communities.

“There’s a reason why the state of Michigan was initiated into the United States in 1837. In order to complete the statehood process, they had to extinguish Indian title (land ownership) to the Lower Peninsula and ultimately half of the Upper Peninsula as well,” Fletcher said at the event. “So that is a treaty of one of approaching 400 total treaties between the United States and Indian tribes in the United States. It’s not the only treaty that the tribal communities here in Michigan or in this area signed, but probably the most important one.”

It was an explicit acknowledgment that the United States was entering into a treaty with a government, a sovereign entity, known as an “Indian Tribe,” Fletcher explained. The Commerce Clause in The Constitution gave Congress the authority to “regulate commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.” Fletcher said the clause indicates that the founders of the U.S. acknowledged Indian tribes as governing entities with sovereign powers.

“The fact that we were considered nations that could enter into a treaty was an acknowledgment by the United States of sovereignty — an acknowledgment that has never gone away,” he said. “It still remains for the purposes of the United States, we are still sovereign governmental entities and have been at least since 1836, if not before.”

Other topics Fletcher touched on in the hour-long discussion were tribes fishing, hunting, and land rights, the treaties that followed after 1836, and the impacts those treaties had on indigenous communities in the last century.

“In the 1830s when Andrew Jackson was the president of the United States, there was a period called the removal era, and that’s when the Cherokee Trail of Tears happened, that’s where many, if not the mass majority of tribal nations east of the Mississippi river, were forcibly moved to the West, that’s why there’s 38 Indian tribes in Oklahoma instead of about five or six, or dozens in Kansas or Iowa tribes that are really from the Great Lakes area…” he said. “We were able to avoid that for the most part…” The GTB is still seeking its day in court to sue the U.S. for the loss of reservation lands that were guaranteed by an 1855 treaty and was later taken by the U.S. without any compensation. The tribe’s claims are based on the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution which prohibits the federal government from taking property rights without just compensation, and is seeking monetary compensation for the wrongdoing.

“We got 10.5 cents an acre for the lands sold during the treaty of 1836… The differences between the U.S. value that they acquired in this land and what we got, that’s the dark matter and the duty of protection,” he said. “That’s the reason the United States must fund healthcare and housing, law enforcement, job training, and education. They promised to do so, it’s contained in the treaty when it says ‘our tribal nation comes under the protection of the United States’ that is a legal term of art from customary international law that says the United States owes an enormous amount to tribal nations who entered into these treaties.”